The Mind as the New Battleground for Individual Rights

by: Richard M. Marsh, Jr., Associate Editor, MTTLRFrom its beginnings, this country has created laws designed to protect the individual. The U.S. Constitution itself was amended to include provisions guaranteeing certain basic individual freedoms. Over time, new laws and flexible judicial interpretations have balanced the protection of individual rights against new technological developments. However, there are breakthroughs currently available and innovations on the horizon which threaten to upset the carefully constructed balance. Specifically, neuro-scientific advancements now allow access to an individual’s mind. One example is fMRI technology which, now or very soon, will be capable of invading one’s mind and seeing thoughts as they happen. 1 Various news agencies report that scientists can currently “see” when a subject recognizes 2 or thinks about a photo, 3 is sexually aroused, 4 or lies. 5 Other reports indicate that refinements are not too far away which will enable users to perceive individual thoughts. 6 Another example is propranolol, a drug which can effectively dampen or erase prior memories. 7 A third example involves brain to computer interfaces which have the ability to monitor and change brain wave patterns. 8 While these developments can produce significant advantages for individuals and society, potential misuses could quickly unravel into serious violations of individual rights. Mind invasive technology opens the door to practices which could violate many of the rights enshrined in the Bill of Rights. For example, it is easy to imagine a scenario where fMRI technology could be used to violate a civilian’s right to privacy, initiate an unreasonable search in violation of the Fourth Amendment, or even run afoul of the self-incriminating clause of the Fifth Amendment. Furthermore, the need for protection from mental invasion is not only based on the constitution. For example, if used in interrogation techniques, fMRI technology could violate rights protected under international standards, including the International Human Rights Law. 9 Current legal protection may or may not ensure against these violations. For example, in Kyllo v. United States, 10 the Supreme Court ruled that using sense-enhancing technology (an infrared camera) without a search warrant to “see” inside a home violated the Fourth Amendment. 11 Justice Scalia applied the Katz test and stated “obtaining by sense-enhancing technology any information . . . that could not otherwise have been obtained without physical intrusion into a constitutionally protected area . . . constitutes a search – at least where (as here) the technology in question is not in general public use.” 12 The last phrase included by Justice Scalia could be interpreted to imply that the more popular a technology becomes, the less likely that courts will interpret the use of it by police as a search. Taken to the extreme, if the technology becomes common place, an fMRI search by police may become a “reasonable search” for purposes of the Fourth Amendment. However, the nature of fMRI technology is so invasive of an individual’s thoughts that the use of mind-reading technology should never be considered “reasonable.” These illustrations only scratch the surface of the many dilemmas awaiting us as science continue to march forward. Nevertheless, the severity of the potential harms should advise us to be cautious and safeguard our fundamental rights as we implement each new innovation.

1 FMRI technology can also be used to change individual behavior. Jason Ponton, Mind Over Matter, With a Machine’s Help, N.Y. Times, Aug. 26, 2007.

2 CNN.com, See it, imagine it -- it's the same to your brain, Nov. 2, 2000.

3 Faye Flam, Your Brain may Soon Be Used Against You, Phila. Inquirer, Oct. 29, 2002.

4 ScienceDaily.com, Pedophiles Have Deficits In Brain Activation, Study Suggests, Sep. 24, 2007.

5 BBC News, Can brain scans detect criminals?, Sept. 21, 2005.

6 BBC News, Brain scan 'can read your mind', Feb. 9, 2007.

7 Adam J. Kolber, Therapeutic Forgetting: The Legal and Ethical Implicaions of Memory Dampening, 59 Vand. L. Rev. 1561, 1574-78 (2006).

8 Emmet Cole, Direct Brain-to-Game Interface Worries Scientists, Wired, Sept. 5, 2007.

9 See Sean Kevin Thompson, Note, The Legality of the Use of Psychiatric Neuroimaging in Intelligence Interrogation, 90 Cornell L. Rev. 1601 (2005).

10 Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27 (2001).

11 Id. at 40.

12 Id. at 34.Labels: privacy

The Promise of Electronic Wills

by: Keven DuComb, Associate Editor, MTTLRCurrently only one state, Nevada, has a statutory provision allowing for electronic wills. 1 Nevada was probably a little excessive in requiring at least one "authentication characteristic"--which is essentially an electronic biological marker attached to the electronic will--in addition to the traditional will requirements. 2 Nevada's strict and costly requirements, coupled with the exclusion of "wills, codicils, or testamentary trusts" from the Electronic Signatures in Global and National Commerce Act (E-SIGN) 3 has led academics to avoid much discussion of electronic wills. However, a 2003 decision of the Tennessee Court of Appeals, holding that a computer-generated signature using a stylized font satisfied the signature requirement, has created some slight interest in the future of electronic wills. 4I think the states should enact statutes providing for electronic wills, but that they should provide a way for their citizens to upload the documents onto a secure web database. I believe the use of a secure website would cure most of the problems that could arise if courts were forced to probate any random document purporting testamentary intent found on a decedent’s personal computer. At the same time, this new approach would still create an easier, more cost-efficient method of will creation. Section 1-102(b) of the Uniform Probate Code states that "[t]he underlying purposes and polices of this Code are: . . . (2) to discover and make effective the intent of a decedent in distribution of his property." 5 Generally, this means that courts would like to distribute an estate in accordance with a decedent's wishes, so long as those wishes are clearly stated in a manner that substantially fulfills the requirements of a will. 6 The initial aversion to electronic wills seems to be a carry-over from the aversion to audio and video recordings as legitimate forms of will creation. 7 However, unlike audio and video recordings, which have always been at odds with the writing requirement, wills created on a computer do satisfy the writing requirement. The problem is that electronic wills are at odds with the signature requirement. E-SIGN and the various state laws dealing with electronic signatures enable Americans to conduct daily business transactions, renew driver’s licenses, pay taxes, and even declare ourselves organ donors online. So, why does E-SIGN exempt "wills, codicils, or testamentary trusts?" 8 Gerry Beyer and Claire Hargrove suggest that there are generally five barriers (technical, social, economic, motivational, and obsolescence) to the acceptance of electronic wills. 9 I think the creation of a secure, state-owned, electronic database for wills could go a long way towards breaking down these barriers. The technical worries stem from Nevada’s stringent "authentication characteristic" requirement, which is too far ahead of the available technology. 10 I would argue, along with other commentators, 11 that applying E-SIGN to wills and will substitutes is the solution. I feel that paying taxes or becoming an organ donor is right up there with will creation on the importance scale. Neither of the former tasks requires biometric authentication; passwords or pin numbers are sufficient. The judicial remedies available to combat fraud in traditional will contests will still be available for situations where it seems apparent that an interested party stole a password and uploaded a new or altered will. Additionally, many of the other online safeguards employed by banks, such as security question prompts after a user enters their password and email notifications when there is activity on the account, could help reduce fraud. The economic and motivational barriers are similar in that they are a creation of the narrow view that electronic wills are merely a tool to improve the estate planning attorney’s bottom line. 12 I would urge the state governments to take the lead because they could provide a cheap, efficient alternative for lower income citizens to give effect to their final wishes. Plus, once the system is up and running, it might prove to be an invaluable tool to practicing attorneys, who could use the system to "e-file" all sorts of court documents, a practice urged by some commentators. 13Beyer and Hargrove’s concern over the obsolescence barrier is legitimate if we are looking to give effect to every testamentary document found on a decedent’s computer, discs, flash drive, or blackberry. 14 However, that is precisely the reason I urge the use of a centralized, secure database. While the documents sit in the electronic vault of the state’s servers, any necessary technology updates can be made to ensure that any document in the "vault" can be accessed at the required time. Adequate back-up procedures would be used, but for those citizens worried about a computer crash resulting in the loss of their will, a state could charge a reasonable fee to print and store a hardcopy of an electronic will. At least one state currently charges a small fee if you would like to file your traditional will at the courthouse. 15If the state governments take the lead to implement the system I have described, then the social barrier should be of no concern because there will be no pressure for the older generation of lawyers and clients to change their ways. 16 As I have stated, I urge this new system only to provide an orderly and efficient method for lower income people to dispose of their property upon their death. Finally, there is an additional barrier to my plan not discussed by Beyer and Hargrove. How will a person uploading an electronic will onto the state’s database comply with the witness requirement? At this time, I have not fully formed an absolute theory regarding this problem, but there are certainly many possibilities. For instance, the witnesses could upload their signatures separately with different passwords. The witnesses could login separately, view the will uploaded by the testator, and attest that the document they viewed is the last will and testament of the testator. Or, perhaps, the testator could bring the document in electronic format to a Secretary of State or DMV office and two employees at the office could view the document, attest to the authenticity and upload the document into the state’s database. This latter option would also go a long way in preventing fraud, but would be more difficult and costly. In summation, I would urge states to enact statutes providing for electronic wills, but argue that the "signature requirement" should not be so strict as to make the creation of an electronic will prohibitively costly. Formal wills are already a luxury of the rich; the state should step in to provide a cheap, efficient method for lower income people to dispose of their estates. Further, it is my hope that these initial thoughts will spur more research and analysis in the area of electronic wills and bring forth more ideas about how to effectively implement a program like the one envisioned in this post.

1 Nev. Rev. Stat. § 133.085 (2001).

2 Id.

3 15 U.S.C. § 7003 (2000).

4 Taylor v. Holt, 134 S.W.3d 830, 834 (Tenn. Ct. App., 2003).

5 Unif. Probate Code § 1-102(b) (1993).

6 Matter of Will of Ranney, 589 A.2d 1339, 1344 (N.J. 1991)

7 Gerry W. Beyer & Claire G. Hargrove, Digital Wills: Has the Time Come for Wills to Join the Digital Revolution?, 33 Ohio N.U. L. Rev. 865, 886 (2007).

8 15 U.S.C. § 7003.

9 Supra note 7, at 890-96.

10 Id. at 890-91.

11 See, Stephen E. Blythe, Singapore Computer Law: An International Trend-Setter with a Moderate Degree of Technological Neutrality, 33 Ohio N.U. L. Rev. 525, 561 (2007) (urging Singapore to eliminate similar will and trust exclusions in its electronic signature law). See generally, Mary W. Baker, Where There’s a Will, There’s a Way: The Practicalities and Pitfalls of Instituting Electronic Filing for Probate Procedures in Texas, 39 Tex. Tech L. Rev. 423 (2007).

12 Beyer & Hargrove, supra note 7, at 892-93.

13 See generally, Baker, supra note 11.

14 Beyer & Hargrove, supra note 7, at 893-95.

15 Family Property Law: Cases and Materials on Wills, Trusts, and Future Interests Page 5-18 (Lawrence W. Waggoner et al. eds., 4th ed. 2006).

16 Beyer & Hargrove, supra note 7, at 891-92.

Labels: electronic signatures, wills

Copyright Reform Part 2

by: Professor Jessica Litman

Professor of Law, University of Michigan Law SchoolIn part 1, I explained some of the appeal of seeking to begin a copyright reform process by agreeing on a set of copyright principles to guide lawmakers in their drafting. In the intensely polarized environment that has come to characterize the copyright bar, confining a group’s attention to copyright principles may be one way to begin a productive conversation. Last spring, Boalt Professor Pamela Samuelson recruited a group of copyright experts with diverse views to come together and discuss copyright reform, with the ultimate goal of producing such a set of copyright principles. I’m a member of that group. One of our first homework assignments was to write and circulate individual drafts of appropriate copyright principles. In this initial stage, the goal was not for each of us to come up with a comprehensive Restatement of wise copyright law. Rather, we agreed that each of us would write down one or more principles that we believed should be reflected in the group’s final work product. The draft that I sent to the other members of the group follows. The draft does not represent what I would write if I could use a magic wand to replace the words in title 17 with words of my choosing. It is, instead, an attempt to articulate principles on which copyright experts across the copyright political spectrum might be able to agree. I agreed to post the draft here, because I’m interested in your comments. Preliminary draft of copyright principlesThe copyright law grants exclusive rights that are bounded in time, subject matter and scope. Some ambiguity in the location of those boundaries is probably inevitable, since technological progress introduces new possibilities, and the prospect of lobbying to expand or contract extant rights is always on the horizon. To the extent possible, boundaries should be clear, since ambiguities can deter investment in and exploitation and enjoyment of copyrighted works. A functioning copyright system requires that there be easy ways for people who want to make lawful licensed uses of works to find out to whom they need to apply for permission. The U.S. law used to rely on indivisibility, notice, registration, and recordation to perform those functions. It has also introduced a variety of compulsory licenses to obviate the need to seek permission to use some works in some markets. Other jurisdictions rely on limited alienability or/and a multiplicity of collecting societies to perform these functions. The copyright system needs some mechanism or mechanisms to do this job. Exclusive rights that are ambiguous in scope exacerbate the problems posed by rights holders who are difficult to identify, and vice versa. The exclusive rights granted by copyright law should encourage creation and dissemination of works by ensuring that copyright owners have meaningful opportunities to control the direct commercial exploitation of their works. Copyright owners should not necessarily be entitled to control all incidents of direct exploitation of their works. Resale of books and paintings, for example, is direct commercial exploitation of copyrighted works that has traditionally been sheltered from copyright owner control by the first sale doctrine. The exclusive rights granted by copyright law should encourage reading, viewing, watching, listening to and learning from copyrighted works by preserving individuals’ freedom to read, view, watch, listen to and otherwise enjoy copyrighted works as they want to without being subject to pervasive copyright owner control of reading, viewing, etc. Reading freely, however, is not necessarily the same thing as reading for free. The exclusive rights granted by copyright should encourage investment in new markets and modes of enjoying copyrighted works by excluding most indirect exploitation of copyrighted works from copyright-owner control. The makers and sellers of trumpets have built their business model on the foundation of band music that was written and is controlled by someone else. The availability of trumpets has increased the market for and popularity of band music, to the benefit of composers, trumpet players, and trumpet music fans. Insofar as possible, the copyright law should neither give the owners of band music copyrights the right to control the design, manufacture or sale of trumpets, nor give the makers and sellers of trumpets the right to control the sale or performance of band music. The public invests in the copyright system both by granting rights to copyright owners through the enactment of copyright laws, and by complying with the laws its Congress enacts. If the public perceives copyright law to give it a poor return on its investment, it may well respond by divesting – either pressing its elected representatives to enact additional limitations and privileges or simply failing to comply with rules it no longer perceives as legitimate. Enforcing copyright law in an atmosphere of public cynicism about the legitimacy of the law is a difficult task. A public that complies with copyright only because it’s afraid of the copyright police will soon find ways to evade or restrain the copyright police. (Recent efforts to enforce copyrights against individual consumers alleged to have infringed copyrights over peer-to-peer file sharing networks, for example, have garnered significant press coverage. Insofar as people are able to make accurate measurements, these efforts do not seem to have reduced the volume of unauthorized peer-to-peer file sharing, nor to have significantly increased public respect for copyright law.) The long-term health of the copyright system, thus, requires that members of the public believe that their investment in copyright is well spent. One key feature of copyright laws that have public confidence is a balance between the copyright owners’ exclusive rights to control the exploitation of their works and the public’s freedom to enjoy those works. (In general, countries other than the U.S. that phrase their exclusive rights in broader terms than the United States does have needed more numerous explicit exceptions for members of the general public.) The public appears to believe that copyright exclusive rights are already very broad, and decades of public relations efforts don’t seem to have persuaded people that copyright gives creators and disseminators too little. If copyright is to retain or regain its legitimacy, any broadening of exclusive rights probably needs to be balanced by an increase in personal freedom to enjoy copyrighted works. Labels: copyright, legal reform

Copyright Reform Part 1

by: Professor Jessica Litman

Professor of Law, University of Michigan Law SchoolIf you hang out among copyright lawyers, you’ll notice widespread agreement that the current copyright statute, enacted more than 30 years ago in 1976 and amended piecemeal in the years since, isn’t working very well. (That doesn’t mean that copyright lawyers agree on which parts need fixed.) 1 The statute treats dissemination of works over digital networks especially poorly. That’s unsurprising; extensive use of digital networks post-dates the statute’s enactment. Yet, you’ll also notice widespread discomfort with the prospect of asking Congress to undertake the project of wholesale copyright revision. That discomfort is only partially due to the fact that copyright revision is lengthy and expensive. The number of interests affected by copyright is huge, and the complaints those interests have with the current regime are diverse. Overhauling the copyright statute took more than 20 years the last time Congress tried it, and there’s no reason to think it could happen more quickly today. More importantly, the large role played in copyright lawmaking by lobbyists for important copyright actors has in the past produced statutes that are neither models of clarity nor well-designed to weather the pressures of technological progress. It is difficult to look at section 114 of the current copyright statute, 2 for example, and come up with anything nice to say about it. Moreover, history teaches that in the course of any major copyright revision, new copyright-affected players will pop up and demand that the law be reshaped to accommodate their needs. In the revision process that culminated in the enactment of the 1909 copyright act, the manufacturers of phonographs and phonograph records nearly derailed the entire effort until they were satisfied with the statute’s treatment of them. Multiple attempts to modernize the copyright law during the 1920s and 1930s foundered because new players ASCAP and radio broadcasters could not agree on anything. In the revision process that led to the 1976 Act, broadcast television and then cable television showed up and demanded special treatment; copyright revision ground to a halt until they got it. The prospect of the upstart new copyright interest may be especially scary today because there are tens of millions of ordinary people whose use of YouTube and peer-to-peer file sharing networks means they have direct personal interests in the copyright law. Nobody has succeeded in mobilizing them into a significant political force, but the majority of them are over 18, and many of them vote. It’s entirely possible that over the course of a multi-year, highly publicized copyright reform effort, the interests of ordinary voters could end up playing a more than a nominal role. One can imagine circumstances in which a new awareness on the part of Congress that voters care about copyright could move the law pretty far from where current players would like to see it go. Thus, it is unsurprising that the perceived need for copyright reform combined with widespread reluctance to involve Congress in the effort, at least at the outset, has generated a host of extra-legislative copyright reform efforts. Some of these efforts have involved taking adventurous positions in litigation, in the hope of persuading courts that the law already means what one wishes it did. 3 Some of these efforts have involved using private agreements to contract around inconvenient statutory defaults. 4 Some have involved committing the United States in trade negotiations to take particular positions on copyright enforcement, and then seeking to import those commitments as a gloss on the meaning of current law. 5A different approach seeks to generate a menu of principles to guide later congressional reform. A group may draft copyright principles as part of an advocacy effort 6 or as an effort to steer legislative drafting in particular directions or away from others. 7The copyright bar has grown increasingly polarized over the past 15 years. 8 Precisely because of that polarization, a project designed to gather a group of copyright experts and charge them with generating a list of copyright principles has features that make it appealing across the copyright political spectrum. First, because the effort involves articulating principles of copyright law, the power and money imbalance between different interests looms smaller, blunting the influence of what Larry Lessig has called “all the money in the world.” 9 Second, even those with well-developed lobbying muscles have reasons to prefer conversing with other copyright specialists rather than a more general crowd. There’s probably some truth to the charge that we who practice, teach, or write about copyright law for a living have all drunk the copyright Kool-Aid®. 10 Copyright lawyers, as a group, are less likely to challenge the received copyright wisdom, and less likely to propose that copyright-affected players adopt radically new business models. Finally, casting a project as a pursuit of copyright principles allows participants to try to ferret out the issues on which they agree and paper over or vague out the issues on which agreement proves impossible. One sign that copyright reform is on the horizon is that copyright principles projects are springing up, trying to figure out a way to generate something that will prove useful. I don’t mean to impugn such projects – indeed, as I’ll explain in the next post, I’ve been working with one myself. Editor: Part 2, in which Professor Litman attempts to "articulate principles on which copyright experts across the copyright political spectrum might be able to agree," will publish tomorrow.

1 Compare, e.g, Pamela Samuelson, Preliminary Thoughts on Copyright Reform, Utah L. Rev. (2007) with, e.g., David Nimmer, Codifying Copyright Responsibly, 51 UCLA L. Rev. 1233 (2004) and Protecting Copyright and Innovation in a Post-Grokster World: Hearing Before the Senate Comm. On the Judiciary, 109th Cong. (Sept. 28, 2005) (testimony of Marybeth Peters, Register of Copyrights).

2 17 U.S.C. § 114 (“Scope of Exclusive Rights in Sound Recordings”).

3 See, e.g., Capitol Records v. Bertelsmann, 377 F. Supp. 2d 796 (N.D. Cal. 2005); Viacom International v. YouTube, Inc., No. 07-CV-2103 (S.D.N.Y. filed March 13, 2007); Capitol Records, Inc. v. Thomas, No. 06-CV-1497 (D. Minn. 2007).

4 CBS, Inc. et. al, Copyright Principles for User-Generated Services (Oct. 18, 2007); the GNU General Public License (June 29, 2007); Microsoft, Inc., Microsoft Windows Vista Home Basic English End User License Agreement (visited Nov. 12, 2007); see generally Prof. Margaret Jane Radin, The Evolution of Contracts in the Digital Era (Seminar, Fall 2007).

5 See, e.g., Brief Amicus Curiae Americans for Tax Reform in Cartoon Network, LP v. Cable News Network, LP, No. 07-1480-CV(L) (2d Cir. filed July 11, 2007) at 15-16.

6 E.g., Adelphi Charter on Creativity, Innovation and Intellectual Property (Oct. 13, 2005); CBS, Inc. et. al., Principles for User-Generated Content Services, supra note 4; Center for Democracy and Technology, Protecting Copyright and Internet Values: A Balanced Path Forward (Spring 2005); EFF et. al., Fair Use Principles for User-Generated Video Content (Oct. 31, 2007).

7 See National Information Infrastructure Task Force Working Group on Intellectual Property, Public Hearing on Intellectual Property Issues Involved in the Information Infrastructure (Nov. 18, 1993), (testimony of Gary J. Shapiro, Home Recording Rights Coalition); id. (testimony of Ronald J. Palensky, Information Technology As’sn of America).

8 See Jessica Litman, War and Peace: The 34th Annual Donald C. Brace Lecture, 53 J. Copyright Socy 1 (2006).

9 LAWRENCE LESSIG, FREE CULTURE 241 (2004).

10 Kool-Aid® is a registered trademark of Kraft Foods. :-)

Labels: copyright, legal reform

The University of Michigan Wants You To "Be Aware You're Uploading"

by: Kurt Hunt, Blog Editor, MTTLRIn October of 2007, the University of Michigan announced a new “Be Aware You’re Uploading” (BAYU) program “to notify users of University networks that they might be uploading” to peer-to-peer networks. 1 The service, which will automatically e-mail students in residence halls when the University network detects P2P uploading, was said to serve three goals: (1) “to help users avoid unwittingly uploading,” (2) to help users upload lawfully, and (3) to help students “be mindful of the risks” of using P2P. 2Although University of Michigan assistant general counsel Jack Bernard reaffirmed that the school’s “goal is to educate our students so they can understand their choices, risks, and responsibilities,” 3 it’s worth taking a closer look at the likely (and plausible) results of BAYU to determine if “education” is indeed the goal being served. BAYU’s first two stated goals—to help users avoid unwittingly uploading, and to help users who wish to upload do so lawfully 4—seem sufficiently focused on the well-being of the students to fit within the University’s description of the service’s ultimate purpose. The third, however, is more questionable. The stated goal of helping students “be mindful of the risks” of using P2P technology is described by Mr. Bernard as simply educating students. 5 While the educational result is undeniable, I would argue that affirmatively sending an e-mail to students warning them to "be mindful of the risks" of the P2P suggests that education is not the primary goal of the system. Deterrence is. BAYU seems designed to intimidate. It puts students on notice that there is no anonymity in the residence halls, that their activities are noticed, and that their activities can be traced to them personally. It is far more personal and invasive than is necessary for mere "education." This may seem like a quibbling difference in the framing of the goal, but its implications for BAYU should not be ignored. If BAYU is primarily serving educational goals, that implies that the University of Michigan is indifferent--or at least is not motivated by its opposition--to uploading of unauthorized content to P2P systems. The fact is, however, that the University is not indifferent. Unauthorized file sharing from residence halls causes administrative hassles, potential legal liability, and political pressure from the RIAA and related groups. 6 The University, through Mr. Bernard as well as mass e-mails to students, has repeatedly stressed that it "does not condone unlawful peer-to-peer file sharing" (hardly a surprise). 7 Both for policy reasons and practical reasons, the University has every possible motivation to reduce unauthorized filesharing from its residence network. At the same time, it recognizes that publicizing BAYU as a "deterrent" to unauthorized file sharing would likely stir dissent within the student community. Hence: "education." This shift from education to deterrence has important implications for the program’s success. First, it makes success hinge on a reduction of unauthorized file sharing—increased student knowledge of the risk is insufficient. Second, if BAYU proves successful in this respect, the obvious benefits to the University might inspire other schools to adopt similar methods of deterrence (with some perhaps not being wrapped in such rosy clothing). What then? If BAYU proves to be successful at deterring unauthorized filesharing and is imitated at many major universities, as it likely would be, the P2P market might see a dramatic reduction in the number of unauthorized uploaders. Studies have confirmed what common-sense tells us: college students make up a disproportionately high percentage of the unauthorized P2P market. 8 Even accounting for the fact that not all college students connect to the internet via a University network, 9 that could be a substantial number of potential uploaders that would be actively deterred. In other words, the spread of BAYU could help bring content owners one step closer to the goal of containing unauthorized file sharing. Whether it's proper for universities to take this action is a broad question of policy that I don't pretend to address here. It's enough for now to point out that BAYU may not be as snuggly as the University portrays it, and that its success may have a wide effect on the future development of the P2P market.

1 U-M BAYU: Be Aware You’re Uploading, http://bayu.umich.edu/basics.php.

2 Id.

3 Jack Bernard, ’U’ Puts Students First, The Michigan Daily, Oct. 31, 2007, available at http://media.www.michigandaily.com/media/storage/paper851/news/2007/10/31/Viewpoints/u.Puts.Students.First-3067804.shtml.

4 U-M BAYU: Be Aware You’re Uploading, http://bayu.umich.edu/basics.php.

5 Jack Bernard, ’U’ Puts Students First, The Michigan Daily, Oct. 31, 2007, available at http://media.www.michigandaily.com/media/storage/paper851/news/2007/10/31/Viewpoints/u.Puts.Students.First-3067804.shtml.

6 See, e.g., Press Release, Recording Industry Association of America, Pre-Lawsuit Letters Sent in New Wave Targeting Music Theft on 19 Campuses (Oct. 18, 2007), http://www.riaa.org/newsitem.php?news_year_filter=&resultpage=&id=E549F223-3648-E92C-0CA2-7BFAFC2DB352 (RIAA sent 20 “pre-litigation settlement letters” to University of Michigan students in October, 2007); Press Release, Recording Industry Association of America, RIAA Pre-Lawsuit Letters Go to 22 Campuses in New Wave of Deterrence Program (April 11, 2007), http://www.riaa.com/newsitem.php?news_year_filter=&resultpage=4&id=7408966D-245D-A17D-4869-C0DB1E7ADA97 (RIAA sent 23 “pre-litigation settlement letters” to University of Michigan students in April, 2007).

7 See, e.g., Jack Bernard, ’U’ Puts Students First, The Michigan Daily, Oct. 31, 2007, available at http://media.www.michigandaily.com/media/storage/paper851/news/2007/10/31/Viewpoints/u.Puts.Students.First-3067804.shtml; Letter from Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, University of Michigan, to students of the University of Michigan (March 8, 2007), available at http://michiganfreeculture.files.wordpress.com/2007/03/riaa11.jpg?w=310&h=257.

8 Jack M. Germain, Big Pirate on Campus, E-Commerce Times, June 5, 2007, http://www.ecommercetimes.com/story/57678.html (citing a study by marketing firm NPD).

9 American Council on Education, Paying for College, http://www.acenet.edu/Content/NavigationMenu/ProgramsServices/CIP/PayingforCollege/College_Prices.htm (“about 25 percent of undergraduates live on campus”).

Labels: copyright, education, p2p

YouTube's Apology

by: Oscar A. Lara, Associate Editor, MTTLRGoogle and YouTube are currently facing a class action lawsuit for copyright infringement. Among the parties claiming infringement are the Football Association Premier League, England’s most popular soccer league, and Viacom, which owns MTV and Comedy Central. The result of this lawsuit could change the way the safe harbor provisions of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) are examined. 1 In this case, a liberal reading of the statute would benefit the public. The heart of the claim is that YouTube infringes the copyrighted works uploaded by altering the posted videos. 2 It is also alleged that YouTube secondarily infringes these works by promoting these infringing uses, receiving advertising revenue through these infringements, and by not implementing reasonable measures that could eliminate or reduce the uploading of infringing works. 3 Google and YouTube respond that they do not infringe because they remove the copyrighted works as soon as they are notified. 4 They also claim that they fall within the safe harbor provisions of the DMCA. 5 Usually, when confronted with similar lawsuits, Google has been able to rely on the safe harbor provisions of the DMCA. 6 However, these provisions may not be able to save Google in this case. Considering that Google does profit from people using YouTube and is aware that people could abuse its server to infringe others' works, Google may not be able to meet the knowledge requirements set forth under the safe harbor provisions of the DMCA. 7 This is assuming that the safe harbor provisions are examined under a strict reading. The court, however, should examine these provisions more loosely. While it is true that Google does profit from YouTube, it is not necessarily from the number of infringed videos uploaded. Aside from the millions of people who visit YouTube, 8 Google profits from YouTube from the advertisements present on its main home page as well as those present in the search results. 9 In addition, while Google and YouTube may be aware of the possibility of its users infringing, there is very little they can do aside from what they do now. YouTube would need to check every video that is uploaded, and make sure that it is not infringing on anybody’s copyright. This is difficult in multiple levels. First, YouTube would need to identify whether the work is protected by copyright. Since neither notice 10 nor registration 11 is required for copyright protection, attempting to discover whether a video a particular video is infringing can be a difficult and tedious task. Also, if YouTube does encounter a video that contains parts of a copyrightable work, the video may still fall under the fair use doctrine. 12 YouTube would then need to decide whether the work qualifies as fair use. However, this would require YouTube employees to be judges of what constitutes fair use, or to hire intellectual property experts to do it for them. In either case there is still the possibility of YouTube getting it wrong. Since this is something that should not expected from Google, YouTube, or any service provider in general, they should not be seen to violate the knowledge requirement. Google and YouTube also remove unauthorized videos quickly after they are notified by the copyright holders. YouTube only asks that the copyright owner send in the proper notification requirements listed in the DMCA. 13The goal of Section 512 is to limit the liability that service providers would otherwise incur under regular conditions, because of the internet’s nature. 14 Much of what is uploaded on YouTube is out of their control. It would be asking too much of Google and YouTube to take the certain measures listed above. Even the measures they have recently taken to reduce piracy and infringement raise questions of whether they violate the fair use doctrine. 15 Finding Google and YouTube liable would be a great harm to the public. Google and YouTube could potentially resort to charging for uploading videos in order to compensate for the liability costs. Or, it could lead Google to shut down YouTube. In either case, many people would lose a method of sharing their ideas and creativity to the public. This does not promote "Progress" as the Intellectual Property Clause of the Constitution states. 16 If anything, it might be promoting regress.

1 Section 512 of the DMCA contains the safe harbor provisions that protect service providers from copyright infringement liability. Section 512(a) deals with transmitting, routing, or providing connections for material through a system or network controlled by the service provider. 17 U.S.C.A § 512(a) (1998). Section 512(b) deals with intermediate and temporary storage of material on a controlled network operated by the service provider. 17 U.S.C.A § 512(b) (1998). Section 512(c) deals with information residing on systems or networks at direction of users. 17 U.S.C.A § 512(c) (1998). Section 512(d) deals with information tools. 17 U.S.C.A § 512(d) (1998).

2 Jakob Halpern, Finding a Safe Harbor, 189 N.J.L.J. 1082, 1083 (2007).

3 Id.

4 Jakob Halpern, supra note 2, at 1084.

5 Id.

6 See Field v. Google, Inc., 412 F.Supp. 2d 1106 (D. Nev. 2006) (granting Google’s motion for summary judgment that it qualifies for § 512(b) safe harbor provision for system caching); Parker v. Google, Inc., 422 F.Supp 2d 492 (E.D. Pa. 2006) (finding that Google’s system caching activities fell under § 512(b) safe harbor provision for system caching).

7 Under the conditions set forth in section 512(c)(1), a service provider is not liable if (A) they do not have actual knowledge that the network is being used for infringing, could not know that infringing is occurring on their network, and when they do discover infringing activity, they act quickly to remove it; (B) they do not receive profits from the infringing activity; and (C) they act quickly to remove the infringing content as soon as they are notified by the copyright owners. 17 U.S.C.A § 512(c)(1) (1998).

8 Despite the large number of visitors that YouTube attracts, YouTube does not profit from these visits. See Andrew Ross Sorkin & Peter Edmonston, Google Is Said To Set Sights On YouTube, N.Y. Times, Oct. 7, 2006, at A1, available at 2006 WLNR 17372080.

9 YouTube Videos To Play On Other Sites: Owner Google Hopes To Make Money From Ads Linked To The Clips, L.A. Times, Oct. 9, 2007, at 12, available at 2007 WLNR 19752532.

10 See 17 U.S.C.A. § 401 (1989).

11 See 17 U.S.C.A. § 408(a) (1989).

12 In section 107 of the Copyright Act, also known as the fair use doctrine, Congress placed certain limitations on exclusive rights to copyright ownership. See 17 U.S.C.A. § 107 (1976). Four factors are taken into account: (1) the purpose of the use, such as commercial use or for nonprofit educational use, (2) the nature of the copyrighted work, (3) the amount that is used in relation to the work as a whole, (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. 17 U.S.C.A. § 107 (1976).

13 See YouTube, Copyright Infringement Notification, http://youtube.com/t/dmca_policy, (last visited Oct. 29, 2007).

14 See generally 17 U.S.C.A. § 512 (1998).

15 YouTube has launched a new anti-piracy plan, called the YouTube Video Identification program. This program will detect unique characteristics of the content posted by its users and prevent these videos from being posted if they contain infringing works. Michelle Quinn, YouTube Anti-Piracy Plan: Give Us Videos You Don’t Want Copied, L.A. Times, Oct. 16, 2007, at 1, available at 2007 WLNR 20280958.

16 U.S. Const. art. 1, § 8, cl. 8.

Labels: copyright, dmca, youtube

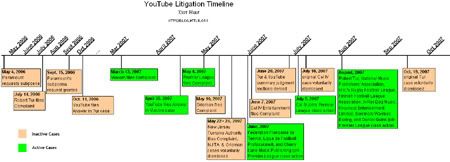

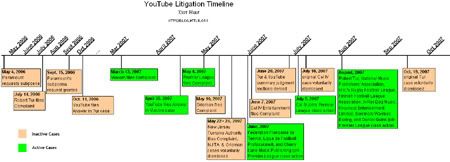

A Timeline of YouTube Litigation

by: Kurt Hunt, Blog Editor, MTTLR1In the ongoing debate about the scope of U.S. copyright law, there is possibly no company more in the spotlight than YouTube. YouTube launched in 2005 as a website where users could "easily upload and share video clips . . . across the Internet." 2 In November, 2006, YouTube was purchased by Google in a $1.65 billion stock-for-stock deal. 3 Now, more than 72 million monthly visitors view more than 100 million videos per day. 4The combination of YouTube's business model (relying entirely on uploaded content) and Google's deep pockets have made the company a lightning rod for litigation. The frenzy of lawsuits has left many confused about who has sued YouTube for what, and about what lawsuits remain relevant. This post is intended to provide a basic overview of the litigation timeline since early 2006, including a basic description of each of the six complaints filed against YouTube. Major developments have been included in the graphical timeline below (click to expand).

Tur v. YouTube5filed: July 14, 2006 dismissed: October 19, 2007 Robert Tur is an independent news videographer, perhaps best known for his footage of the beating of Reginald Denny during the L.A. Riots in 1992 and his footage of the infamous O.J. Simpson white Bronco car chase in 1994. Capturing such socially important moments earned Tur his reputation, but also caused him to struggle against unauthorized uses of his work. In the summer of 2006, Tur was the first to file suit against YouTube on a theory of copyright infringement. Both parties' summary judgments were ultimately denied, but the case was never litigated to completion. Tur voluntarily dismissed the case in the fall of 2007 in order to join the Premier League class action suit against YouTube (discussed below). Viacom v. YouTube6filed: March 13, 2007 Viacom is the corporation that owns MTV, VH1, BET, Comedy Central, and other popular media outlets. Although other similarly-situated content owners had already signed licensing deals with YouTube, 7 Viacom lost its patience after it served more than 100,000 demands to remove unauthorized material from YouTube. 8 Although YouTube complied with the takedown requests, Viacom alleged that users were immediately able to reupload similar or identical content. Shortly afterward, Viacom sued YouTube for allegedly hosting and displaying "more than 150,000 unauthorized clips . . . that had been viewed an astounding 1.5 billion times." 9 The complaint alleged direct infringement, contributory infringement, vicarious infringement, and inducement. 10Because of the scale of alleged infringement and the high profile of the plaintiff, the Viacom case is one of the two important cases pending against YouTube (the other being the Premier League class action, discussed below). Premier League v. YouTube11filed: May 4, 2007 This class action suit for copyright infringement was filed by English Premier League, a major professional sports league from the U.K. While Americans may find it easy to ignore the complaints of a foreign soccer league, this class action has gained considerable inertia. Plaintiffs now include other European sports leagues, Cherry Lane Music Publishing, National Music Publishers’ Association, X-Ray Dog Music, Knockout Entertainment Ltd., Seminole Warriors Boxing, videographer Robert Tur, and author Daniel Quinn. Along with the Viacom case, this is the one to watch. Like all suits alleging copyright infringement by YouTube, this case is likely to turn on the court's reading of Section 512(c) of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. The MTTLR Blog will be publishing an in-depth discussion of the 512(c) safe harbor in relation to the Premier League case tomorrow. Grisman v. YouTube12filed: May 10, 2007 dismissed: May 25, 2007 David Grisman is a world-famous mandolin player (no, really). He played with The Grateful Dead, and has a following in the modern bluegrass scene. In fact, his popularity is such that several videos of him playing were uploaded without authorization to YouTube. In an attempt to replicate the Premier League class action, Grisman and his company Dawg Music filed suit, alleging copyright infringement. The case was voluntarily dismissed two weeks later, due to Grisman's desire to join the Premier League class to establish "a united front." 13New Jersey Turnpike Authority v. YouTube14filed: May 22, 2007 dismissed: May 24, 2007 Footage of a grisly car crash, recorded by cameras operated by the New Jersey Turnpike Authority, was obtained by a YouTube user and uploaded to the website. The NJTA sued YouTube for copyright infringement (without even having first requested YouTube to remove the content). Within days, the NJTA decided there was no use in trying to litigate against YouTube on its own and, like fellow small plaintiffs Tur and Grisman, threw in its lot as a member of the Premier League class. Cal IV v. YouTube15filed: June 7, 2007 dismissed: July 10, 2007 Cal IV Entertainment, LLC, a country music publisher, also sought to establish a class action suit against YouTube. Its concern was that "more than 60 of the copyright songs in its catalog appeared in various forms without the proper license or any authorization." 16 As with most of the independent plaintiffs, Cal IV eventually voluntarily dismissed its action in favor of the Premier League class action.

1 Small portions of this post have been adapted from my forthcoming note. Kurt Hunt, NOTE: Copyright and YouTube: Pirate’s Playground or Fair Use Forum?, 14 Mich. Telecomm. & Tech. L. Rev. ___ (forthcoming Fall 2007).

2 About YouTube, http://www.youtube.com/t/about (last visited Oct. 31, 2007).

3 Press Release, Google, Google to Acquire YouTube for $1.65 Billion in Stock (Oct. 9, 2006) http://www.google.com/press/pressrel/google_youtube.html.

4 YouTube Users Could Share in Ad Revenues, The Daily Mail, Oct. 10, 2006, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/pages/live/articles/news/news.html?in_article_id=409544.

5 Robert Tur v. YouTube, Inc., No. CV 06-4436-GAF (FMoX) (C.D. Cal. July 14, 2006).

6 Viacom International, Inc. v. YouTube, Inc., No. 07CV2103 (S.D.N.Y. March 13, 2007).

7 See, e.g., YouTube Strikes Content Deals, USA Today, Oct. 9, 2006, http://www.usatoday.com/tech/news/2006-10-09-youtube-deals_x.htm; Andrew Ross Sorkin & Jeff Leeds, Music Companies Grab a Share of the YouTube Sale, N.Y. Times, Oct. 19, 2006, at C-1, available at http://select.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FA0F13FB34540C7A8DDDA90994DE404482; Sara Kehaulani Goo, NBC Taps Popularity of Online Video Site, Wash. Post, June 28, 2006, at D-01, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/06/27/AR2006062701750.html.

8 Eric Bangeman, Viacom Demands YouTube Pull Its Videos Down, Ars Technica, Feb. 2, 2007, http://arstechnica.com/news.ars/post/20070202-8756.html.

9 Complaint at 3, Viacom International, Inc. v. YouTube, Inc., No. 1:07CV02103 (S.D.N.Y. March 13, 2007).

10 For a more thorough discussion of the Viacom complaint, see Kurt Hunt, A Guide to Viacom v. YouTube, Clever WoT, March 15, 2007, http://krhunt.blogspot.com/2007/03/guide-to-viacom-v-youtube.html.

11 Football Association Premier League et al. v. YouTube, Inc., No. 1:07-cv-03582-UA (S.D.N.Y. May 4, 2007).

12 Grisman et al. v. YouTube, Inc., No. 3:2007cv02518 (N.D. Cal. May 10, 2007).

13 Declaration of David J. Grisman in Support of Plaintiffs' Motion for Appointment of Interim Class Counsel, Football Association Premier League et al. v. YouTube, Inc., No. 1:07-cv-03582-UA (S.D.N.Y. May 4, 2007), available at http://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/new-york/nysdce/1:2007cv03582/305574/24/3.html.

14 New Jersey Turnpike Authority v. YouTube, Inc., No. 2:2007cv02414 (D.N.J. May 22, 2007).

15 Cal IV Entertainment, LLC v. YouTube, Inc. et al., No. 3:2007cv00617 (M.D. Tenn. June 7, 2007).

16 Complaint at 12, Cal IV Entertainment, LLC v. YouTube, Inc. et al., No. 3:2007cv00617 (M.D. Tenn. June 7, 2007).Labels: copyright, youtube

An Overview of Telecommunications Companies' Involvement in Domestic Espionage: Part II

by: Joseph Eros, Associate Editor, MTTLREditor's Note: This post continues yesterday's Part I, which discussed the background of the litigation against telecommunications companies for their involvement in domestic espionage by the NSA.If the lawsuits are allowed to proceed, the plaintiffs may present testimony from witnesses claiming direct knowledge of AT&T’s close involvement with the NSA. Mark Klein, a retired AT&T technician, filed a declaration describing the installation of a secure room, accessed only by NSA-cleared personnel, in an AT&T switching facility. According to Klein, "the content of all the electronic voice and data" transmitted through AT&T’s switches was transferred into the NSA secure room. 19 Documents presented by former Qwest CEO Joseph Nacchio during his trial on insider-trading charges could also reveal important evidence for the telecom suits: Nacchio claimed that Qwest lost NSA contracts because the company refused to share its customers’ calling information. However, the details of Nacchio’s allegations have so far been revealed only in closed-door court sessions. 20By the time the Ninth Circuit is ready to rule, though, its opinion may be irrelevant. President Bush has called for the planned amendments to FISA to include immunity for the companies who may have shared customer information with the NSA: "[FISA] needs to be changed, enhanced, by providing the phone companies that allegedly helped us with liability protection." 21 The President has said he will not sign any FISA amendments unless they include immunity. 22Although few laws exempting specific industries from liability suits have been passed, there is a recent example. The Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act, 23 passed in October 2005, shields firearms manufacturers from suits for "the harm caused by those who criminally or unlawfully misuse firearm products . . . that function as designed and intended." 24 Its enactment ended lawsuits against gun manufacturers by cities seeking compensation for the costs of gun violence. 25The Senate Select Committee on Intelligence has included an immunity provision into its FISA amendment bill: Notwithstanding any other provision of law, a covered civil action shall not lie . . . and shall be promptly dismissed, if the Attorney General certifies to the court that the assistance alleged to have been provided by the electronic communications service provider was . . . in connection with an intelligence activity involving communications that was authorized by the President during the period beginning on September 11, 2001 and ending on January 17, 2007.26 No committee-approved House version of the bill includes a telecommunications immunity provision. Speaker of the House Pelosi has conditioned such legislation on House investigation of the surveillance program, saying that "you can't even consider such relief unless we know what people are asking for immunity from." 27 Given the continuing disputes with Congress over supervision of classified activities, it seems unlikely that the House would be satisfied with the White House’s explanations the Bush Administration would be prepared to offer. So President Bush and the rest of us will probably have to wait for the Ninth Circuit to see if the AT&T and the other telecommunications companies can be held liable for following the NSA’s orders.

19 Klein Declaration in at Hepting v. AT&T, June 8, 2006, at ¶34, available at http://www.eff.org/files/filenode/att/KleinDecl-Redact.pdf.

20 Andy Vuong, Judge Denied Use of Spying Data, Denver Post, Oct. 11, 2007, available at http://origin.denverpost.com/breakingnews/ci_7141986.

21 President George W. Bush, White House press conference (Oct. 17, 2007), available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/news/releases/2007/10/20071017.html.

22 Peter Grier, Fight Over Court Role in US Eavesdropping, Christian Science Monitor, Oct. 12, 2007, available at http://www.csmonitor.com/2007/1012/p03s02-uspo.html.

23 15 U.S.C.A. § 7901.

24 15 U.S.C.A. § 7901(a)(5).

25 See Leslie Wayne, Smith & Wesson Is Fighting Its Way Back, New York Times, April 11, 2006, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/11/business/11guns.html.

26 Section 202 of the FISA Amendment Acts of 2007, as passed by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence on October 18, 2007, at 45-46, available at http://intelligence.senate.gov/071019/fisa.pdf.

27 153 Cong. Rec. H11653 (daily ed. October 17, 2007) (statement of Rep. Pelosi), available at http://www.gpoaccess.gov/crecord/07crpgs.html by selecting October 17.Labels: espionage, FISA, national security, NSA, privacy, telecommunications

An Overview of Telecommunications Companies' Involvement in Domestic Espionage: Part I

by: Joseph Eros, Associate Editor, MTTLRIn May 2006, USA Today reported that several of the USA’s largest telecommunications companies had been turning over information on "billions of domestic calls" to the National Security Agency (NSA), giving the agency "a secret window into the communications habits of millions of Americans." 1 USA Today’s detailed report confirmed earlier revelations by the New York Times of ongoing monitoring of domestic telephone calls. 2 The exact extent of the monitoring remains unclear (not surprisingly for a highly-classified program); USA Today later reported that it could not "confirm that BellSouth or Verizon contracted with the NSA to provide bulk calling records" although it did confirm AT&T’s involvement. 3Because the calls were mostly between US citizens within the USA, the US government would need a warrant in order to monitor them. The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), 50 USC 1801 et seq, allows warrantless surveillance of the electronic communications of agents of foreign powers either within the USA or outside of it, but a secret FISA court must approve a warrant in order for the communications of a US citizen within the USA to be surveilled. 4Within a few months, over 40 lawsuits had been filed against the major telecommunications companies, mostly by civil liberties groups. Most of these suits were later consolidated into one action in the Northern District of California. 5 The plaintiffs alleged that the NSA surveillance was in violation of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act (ECPA), 18 U.S.C. § 2702(a)(1), 6 Federal laws against eavesdropping on wire and radio communications (18 U.S.C. §§ 2511) 7 and (47 U.S.C. § 605), 8 and FISA, 9 as well as the privacy laws of all 50 states and the District of Columbia. 10 The activists sought statutory damages (for example, the ECPA specifies damages of "no less than $1,000 for each aggrieved Plaintiff or Class Member" (18 U.S.C. § 2707), 11) as well as an injunction "restraining Defendants from continuing to make such unlawful disclosures." 12 This consolidated action awaits further developments in an earlier suit against AT&T’s disclosures to the NSA, Hepting v. AT & T Corp. 13 The government sought dismissal of the Hepting claims based on the state secrets privilege. If information about which call records were disclosed and how the information was gathered could not be presented in court due to its potential to reveal US intelligence methods, the plaintiffs would be unable to prove their claims, and AT&T would be unable to defend itself. 14 This argument succeeded for the government at AT&T in Illinois, where a lawsuit over the alleged disclosures to the NSA was dismissed in July 2006. 15 But in California’s Northern District it failed: Judge Walker held that the subject matter of this action is not a 'secret' for purposes of the state secrets privilege and it would be premature to conclude that the privilege will bar evidence necessary for plaintiffs' prima facie case or AT & T's defense. Because of the public disclosures by the government and AT & T, the court cannot conclude that merely maintaining this action creates a 'reasonable danger' of harming national security.16 The suits could continue, with classified evidence handled by personnel with security clearances following special procedures. 17Unsurprisingly, the Federal government and AT&T appealed. The Ninth Circuit heard arguments on August 15, 2007, and "repeatedly pressed Gregory Garre, the Bush administration's deputy solicitor general, to justify his requests to toss out the suits on grounds they could endanger national security." 18 No ruling is expected for months. Editor: Part II will publish tomorrow. It will address evidence of telecommunications companies' involvement in warrantless NSA espionage, and dissect the debate over whether to extend immunity to those companies.

1 Leslie Cauley, NSA has massive database of Americans' phone calls, USA Today, May 11, 2006, available at http://www.usatoday.com/news/washington/2006-05-10-nsa_x.htm.

2 James Risen and Eric Lichtblau, Bush Lets U.S. Spy on Callers Without Courts, N.Y. Times, December 16, 2005, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/16/politics/16program.html.

3 A Note to Our Readers, USA Today, June 30, 2006, available at http://www.usatoday.com/money/industries/telecom/2006-06-30-nsa_x.htm.

4 U.S. citizens traveling abroad can have their calls monitored with no warrant required, only the Attorney General’s approval. See U.S. v. Bin Laden, 126 F.Supp.2d 264, 279 (S.D.N.Y. 2000).

5 See In re National Sec. Agency Telecommunications Records Litigation, 444 F.Supp.2d 1332 (Jud. Pan. Mult. Lit. 2006).

6 Master Consolidated Complaint Against Defendants AT&T Mobility et al. for Damages, Declaratory and Equitable Relief at ¶90, In re Nat. Sec. Telecommunications Records Litigation, MDL-1791, No. 06-1791 (VRW), 2007 WL 668730 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 16, 2007).

7 Id. at ¶118.

8 Id. at ¶125.

9 Id. at ¶133.

10 Id. at ¶260.

11 Id. at ¶102.

12 Id. at ¶128.

13 439 F.Supp.2d 974 (N.D. Cal. 2006).

14 Id. at 985.

15 Terkel v. AT & T Corp., 441 F.Supp.2d 899 (N.D. Ill. 2006).

16 Hepting v. AT&T, 439 F.Supp.2d at 994.

17 Id. at 1010-11.

18 Declan McCullagh, Appeals court may let NSA lawsuits proceed, CNET News.com, Aug. 15, 2007, http://www.news.com/Appeals-court-may-let-NSA-lawsuits-proceed/2100-1028_3-6202865.html.

Labels: espionage, FISA, national security, NSA, privacy, telecommunications

Making the wireless world more web-friendly

by: Professor Susan Crawford

Visiting Professor of Law, University of Michigan Law School

Member, ICANN Board of Directors

Founder, OneWebDayYour wireless carrier (in the U.S., probably AT&T or Verizon Wireless) has a lot of control over the handset you can use and the applications that can run on that device. In fact, wireless carriers routinely ask for (and get) an enormous slice of the revenue from applications that work on their networks, and they force handset manufacturers to jump through all kinds of hoops in order to be allowed to sell devices that can connect to these networks. (You can’t, usually, buy devices except through the wireless carrier itself.) There has been a great deal of consolidation in the wireless carrier market: twelve wireless carriers that were independent as of 1999 have combined (through merger, spinoff, or joint venture) into four large wireless carriers: AT&T, VZ, (and, far behind in terms of size) T-Mobile and Sprint. AT&T and VZ together control more than half the market and the lion’s share of new subscribers. The competitive picture isn’t great — AT&T and VZ actually charge more per minute than other, smaller carriers (like Sprint). Until the FCC’s 1968 seminal Carterfone decision, which allowed non-AT&T equipment to be connected to the telephone network, consumers were not free to buy and use devices of their own choice for ordinary telephone communications. Carterfone led to the broad use of the modem and the fax machine, and arguably the birth of the commercial internet. But this open attachment regime has not to date applied to the wireless world, as either a legal or practical matter. The wireless carriers are in complete control. This has had bad effects on the ecosystem of the wireless world. It’s essentially a closed system, for both applications and devices. We’ve gotten used to locked phones that cannot be switched between service providers and two year contracts with heavy penalties for early termination. Here’s the Washington Post from this past summer: Currently, the major U.S. wireless carriers, including AT&T and Verizon Wireless, largely decide which Web sites, music-download services and search engines their customers can access on their cellphones. This is accomplished by wireless companies determining which cellphones will receive their services: AT&T, for example, is the only carrier available to users of Apple’s iPhone. This isn’t a great situation for consumers or innovators. Google’s paired announcements yesterday were aimed at addressing this situation in a way that will - ultimately - be very good for Google. First, they said they were releasing a software “stack” - an open software platform called Android - that would be available under an open-source license. The idea is that anyone could adopt that platform (which includes an operating system, middleware, a user-friendly interface, and some applications) and use it on their phones or in their networks. They’ll be releasing tools for developers to use in writing for that stack, which will (they hope) spur the creation of impossibly cool applications that everyone will have to have. They’ll have big developer conferences someday for Android, just like Microsoft does, creating buzz, t-shirts, and a general sense of well-being and connectedness. Second, they announced a large consortium of companies that will help in further developing Android and pushing it out into the world - the Open Handset Alliance. It’s significant that this group includes T-Mobile and Sprint, the smaller guys in the U.S. It’s also significant that some large handset manufacturers (but not Nokia, why?) and chipset creators are involved too. This will give these guys courage to fight the depredations of the current breaking-kneecaps wireless carrier situation in the U.S. I bet the handset manufacturers are feeling some relief. There’s strength in numbers. This is like unionizing to challenge The Man. Yes, Om Malik is right, this is a big PR move. But the goal is to raise things up a level, to make this platform so ubiquitous and crammed with so many great applications (including Google ad-serving thingies) that the incumbents won’t be able to avoid it. Now, nothing guarantees that this platform will stay open. In fact, VZ could adopt it and close it to applications it viewed to be competing with its core services - like Skype. But the hope is that this kind of modular approach will become the norm in the wireless world. In fact, the goal is greater than that - the goal is to make the wireless world much more like the PC world, where there is no necessary connection between transport and content and anyone can introduce the new cool thing. This clearly helps Google. Of course it does. Why would they do it otherwise? There will be new landscapes to plaster with ads, new ways to make money out of disorder. We won’t be able to find a thing or a person we need without Google’s help. But this initiative also leaves room for new Googles to show up in the wireless ecosystem, and to take advantage of new kinds of cheap, portable devices that are much better than what we’ve got now. Maybe I’ll finally be able to afford a cool phone. Labels: fcc, Google, telecommunications, wireless

Who Owns #1?: Do College Football Rankings Receive Copyright Protection as Databases?

by: John Geis, Associate Editor, MTTLRIt’s that time of year again: crisp Saturday afternoons, college football, and the release of the Bowl Championship Series ("BCS") 1 standings. The BCS standings determine who plays for the NCAA Football Division I national championship and are reprinted in newspapers across the country. In 2004, the Associate Press (“AP”) sent a cease and desist letter to the BCS demanding that the BCS refrain from using the AP Poll in its calculations. 2 In its letter, the AP claimed that its poll had copyright protection. While notice is no longer necessary to secure copyright, and, either way, the copyright on the newspaper is sufficient notice for its separate contributions, 3 it remains to be seen whether the rankings themselves are protected by copyright. College football polls, like telephone books and price lists, should be treated as databases under copyright law. U.S. and international copyright law 4 protect the databases as compilations of data, thereby only protecting the database to the extent of its selection and arrangement of data. The Supreme Court ruled that a residential telephone book did not receive copyright protection because the alphabetical listing of names and phone numbers lacked originality, "the sin qua non of copyright." 5 However, the Second and Ninth Circuits have granted copyright protection to the information contained in the Red Book of used car values and Greysheet of coin prices because they were not "pre-existing facts that had merely been discovered…these predictions were based not only on a multitude of data sources, but also on professional judgment and expertise." 6Beginning the copyright protection analysis with polls, the AP Top 25 College Poll is "compiled from votes by 65 sportswriters and broadcasters from across the country." 7 The USA Today Top 25 Coaches’ Poll "is made up of 60 head coaches at Division I-A institutions. All are members of the American Football Coaches Association." 8 The Harris Interactive College Football PollSM is constructed of "a panel of former players, coaches, administrators and current and former media." 9 Each of these polls could make a solid argument that their polls do not discover pre-existing facts. Instead, these polls harness the collective professional judgment and expertise of writers, coaches, players, and administrators to determine an original expression of the Top 25 college football teams. The professional judgment of the voters is expressed in the pre-season rankings and in the adjustment of their rankings each week as teams begin to win and lose. One may argue that the top two or three teams are often identical and the selections are limited to the 119 NCAA Division I teams. Granted, sometimes the voters’ expressions are the same as voters in other polls, but often they are not, as exemplified by the 2003 end of season rankings in which the polls did not agree, and the AP #1, USC, was left out of the national championship game. 10On the other side of the coin toss, however, are the computer rankings. 11 Computer rankings use a computer model to determine the team rankings based on inputs such as wins, losses, margins of victory, and opponents’ wins and losses. While the rankings are "based . . . only on a multitude of data sources," 12 the selection and interrelation of inputs may show some originality and professional judgment. Obviously, rankings solely based on wins and losses would not show the requisite originality. 13 Yet, one could argue that the computer rankings are like the Red Book values in Maclean. However, one must be careful not to blur the distinction between copyright protection for the underlying computer program and protection for the output rankings. That is, does the originality in selecting process inputs transmute the input facts into an original output? Or, are the output rankings sufficiently merged with the underlying computer algorithms to be barred by §102(b)? 14 In the end, computer rankings take in a large number of facts and formulaically translate those facts into other facts, which are then sorted. Facts are not original and, thus, are not copyrightable. Lastly, there are the BCS standings. According to the BCS website, the methodology of the standings "include three components: USA Today Coaches Poll, Harris Interactive College Football Poll and an average of six computer rankings. Each component will count one-third toward a team's overall BCS score. All three components shall be added together and averaged for a team's ranking in the BCS Standings. The team with the highest average shall rank first in the BCS Standings." 15 The BCS would likely argue that the selection of polls and rankings used and that the commission of Harris Interactive to replace the AP Poll in 2005 are sufficiently original to receive protection. However, like computer rankings, the BCS standings are formulaic transformation of pre-existing facts. 16 This in and of itself does not preclude copyright protection, but simple averaging of other rankings is so mechanical and routine as not to require any creativity whatsoever. In reality, the BCS and other "name brand" rankings receive much of their protection under Lanham Act and state trademark laws. After all, no-one really cares how I rank the Top 25. But as rankings have become big business in the BCS 17 and in society in general, 18 determining how much copyright protection rankings may receive will need to be answered. The polls should receive copyright protection for their rankings because they fold in the professional judgment and expertise of the voters. Computer rankings and the BCS, however, simply manipulate pre-existing facts into more unprotectable facts.

1 Bowl Championship Series, http://www.bcsfootball.org/bcsfootball/ (last visited Nov. 5, 2007).

2 Letter from George Galt, Associated Press, to Kevin Weiberg, Bowl Championship Series Coordinator (Dec. 21, 2004), available at http://www.usatoday.com/sports/college/football/2004-12-21-bcs-ap-letter_x.htm.

3 17 U.S.C. § 101(e) (2007). Section 404 states that "a single notice applicable to the collective work as a whole is sufficient to [defeat defendant’s claims of innocent infringement], as applicable with respect to the separate contributions it contains." 17 U.S.C. § 404 (2007). The definition for "collective work" includes a "periodical issue." 17 U.S.C. § 101 (2007).

4 "A 'compilation' is a work formed by the collection and assembling of…data that are selected, coordinated, or arranged in such a way that the resulting work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship." 17 U.S.C. § 101 (2007). "Compilations of data . . . which by reason of the selection or arrangement of their contents constitute intellectual creations shall be protected as such." Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), Jan. 1, 1996, Article 10(2) (1996). Contra Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996, Article 7, Official Journal L 077, 20-28, Mar. 27, 1996, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=CELEX:31996L0009:EN:HTML ("Member States shall provide for a right for the maker of a database which shows that there has been qualitatively and/or quantitatively a substantial investment in either the obtaining, verification or presentation of the contents to prevent extraction and/or re-utilization of the whole or of a substantial part, evaluated qualitatively and/or quantitatively, of the contents of that database.")

5 Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co., 499 U.S. 340, 345 (1991).

6 CDN Inc. v. Kapes, 197 F.3d 1256, 1261 (9th Cir. 1999) (quoting CCC Information Services, Inc. v. Maclean Hunter Market Reports, Inc., 44 F.3d 61 (2d Cir. 1994, cert. denied, 516 U.S. 817 (1995)).

7 Associated Press, AP College Poll Voters, http://onlinenews.ap.org/collegefootball_rankings/voters (last visited Nov. 5, 2007).

8 USA Today, Top 25 Coaches' Poll, http://www.usatoday.com/sports/college/football/usatpoll.htm (last visited Nov. 5, 2007).

9 HarrisInteractive, Bowl Championship Series, http://www.harrisinteractive.com/news/bcspoll.asp (last visited Nov. 5, 2007).

10 Wikipedia, BCS National Championship Game, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/BCS_National_Championship_Game (last visited Nov. 5, 2007).

11 E.g., Jeff Sagarin, NCAA Football Ratings, USA Today, http://www.usatoday.com/sports/sagarin/fbt07.htm (last visited Nov. 5, 2007).

12 CDN Inc. v. Kapes, supra note 6.

13 "[T]he selection and arrangement of facts cannot be so mechanical or routine as to require no creativity whatsoever." Feist, supra note 5, at 362.

14 "In no case does copyright protection for an original work of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work." 17 U.S.C. § 102(b).

15 Bowl Championship Series, BCS Standings, http://www.bcsfootball.org/bcsfb/standings (last visited Nov. 5, 2007).

16 See, ESPN, BCS Standings, http://sports.espn.go.com/ncf/BCSStandings (last visited Nov. 5, 2007).

17 "The share to each conference with an annual automatic berth in the BCS (ACC, Big East, Big 12, Big Ten, Pac-10 and SEC) is approximately $17 million. If a second team from one of those conferences qualifies to play in one of the games, that conference will receive an additional $4.5 million." Bowl Championship Series, 2007-2008 Media Guide, http://www.bcsfootball.org/id/7212064_37_1.pdf.

18 E.g., Fortune 500, Am Law 100, U.S. News & World Reports: America’s Best Colleges and America’s Best Graduate Schools.Labels: copyright, databases

|

|